Why Informed Consent Matters in Minor Surgery for Kids

Oct, 22 2025

Oct, 22 2025

Informed Consent Checklist for Minor Surgery

Informed Consent Checklist

Use this checklist to ensure you've covered all essential components of the informed consent process for minor surgery in children.

Key Takeaways

- Informed consent for minor surgery involves both legal permission from a guardian and, when possible, the child's assent.

- State laws, HIPAA, and AAP guidelines set the legal baseline for consent.

- Clear communication, age‑appropriate explanations, and documented checklists reduce mistakes.

- Common pitfalls include rushing the conversation, using jargon, and ignoring the child's perspective.

- A practical consent checklist helps clinicians stay compliant and builds trust with families.

When a child needs a simple procedure-say, removing a mole or stitching a cut-doctors often think the paperwork is just a formality. In reality, the Informed Consent in Minor Surgery is the process of obtaining permission from a child's legal guardian and, when appropriate, assent from the child before a low‑risk surgical procedure. Skipping or glossing over this step can lead to legal trouble, loss of trust, and emotional trauma for the family. This guide walks you through why consent matters, what the law requires, and how to run a smooth, kid‑friendly consent conversation.

What Exactly Is Informed Consent in Minor Surgery?

At its core, informed consent means a guardian understands the nature of the procedure, the expected benefits, possible risks, and any alternatives-including doing nothing. For minors, the conversation must also consider the child's developmental stage. A 5‑year‑old needs a much simpler explanation than a teenager who can grasp probabilistic risk.

Key elements of a valid consent:

- Disclosure: clear, honest description of the surgery.

- Comprehension: the guardian (and child when appropriate) truly understands what was said.

- Voluntariness: no pressure or coercion.

- Capacity: the legal guardian has the authority to decide.

- Documentation: the consent is signed and dated.

Legal Foundations You Can’t Ignore

Every state has statutes governing medical consent for minors, but they share common threads. Most require Parental Consent is the legal authority granted to a parent or guardian to approve medical treatments for a child. Some states allow mature minors-typically 14‑16‑year‑olds-to consent to certain procedures if they demonstrate sufficient understanding.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) is a professional organization that issues policy statements on child health, including guidelines for consent and assent recommends a two‑step approach: obtain legal consent from the guardian, then seek the child's assent whenever possible.

On the privacy side, the HIPAA is the federal law that protects patients' health information and defines who may share it still applies, meaning the guardian’s access to the child's records must be documented.

Parents, Guardians, and Their Legal Role

Parents are the default decision‑makers, but not all guardians are equal. Biological parents, adoptive parents, and legal custodians all have the same authority, while step‑parents may need a court order depending on the state. If a child is in foster care, the state child‑welfare agency signs the consent.

Best practice: ask the guardian to repeat back the key points. This “teach‑back” method uncovers misunderstandings before they become problems.

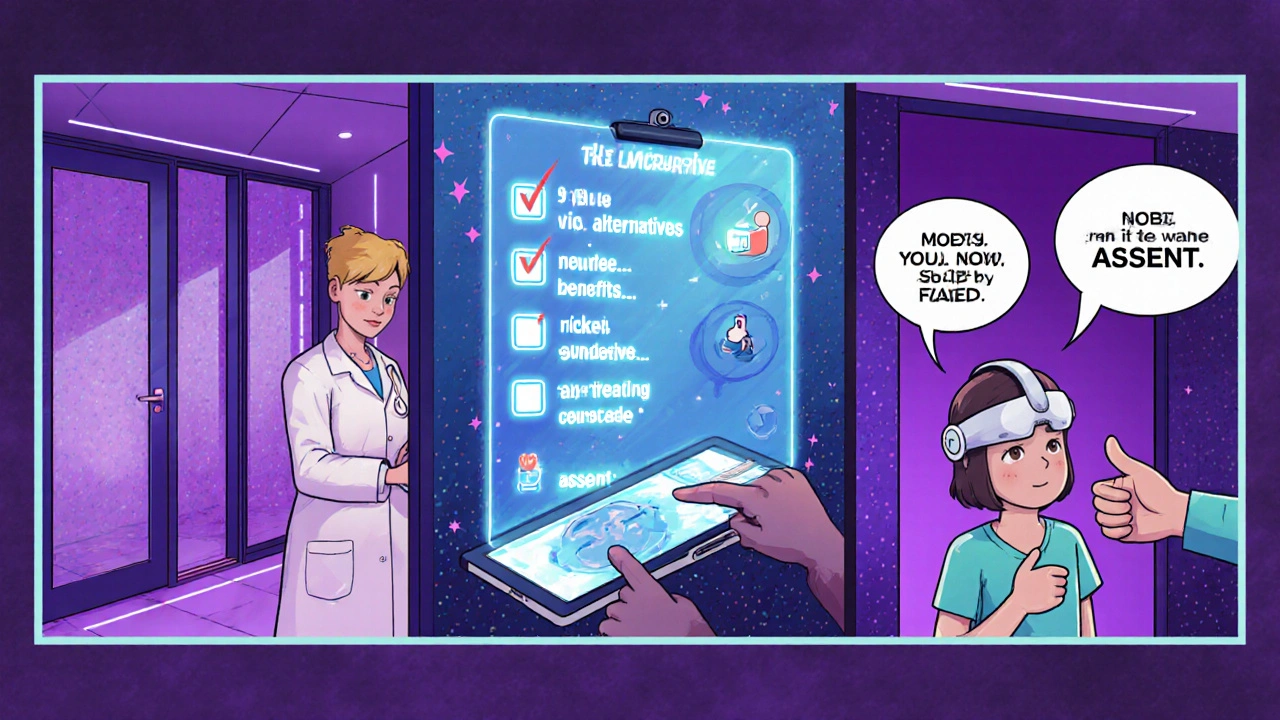

Getting the Child’s Assent (When It’s Possible)

Assent is not a legal requirement in most jurisdictions, but ethically it’s a must‑have. The Assent is the process of involving a child in medical decisions by obtaining their agreement, tailored to their age and maturity demonstrates respect for the child's emerging autonomy.

Tips for gaining assent:

- Use plain language: swap "local anesthesia" for "numbing medicine".

- Visual aids: diagrams or toys that show where the doctor will work.

- Ask open‑ended questions: "What do you think will happen?"

- Allow a “no” answer when the child is too anxious; the guardian can decide to proceed or postpone.

Step‑by‑Step: Conducting a Proper Consent Process

- Prepare the environment: private room, no rush, child‑friendly décor.

- Introduce the team: name, role, and why they’re there.

- Explain the procedure using age‑appropriate language and visual props.

- Discuss risks and benefits: be honest about common side effects and rare complications.

- Review alternatives, including observation or postponement.

- Check comprehension by asking the guardian and child to summarize.

- Obtain signatures on the consent form; keep a copy in the chart.

- Document the conversation in the EMR, noting any questions asked and the child's assent status.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even seasoned surgeons slip up. Here are the usual offenders and quick fixes:

- Jargon overload: replace medical terms with everyday words.

- Rushing the talk: schedule 10-15 minutes for consent, not 2 minutes.

- Assuming assent: always ask the child directly, even if they seem quiet.

- Missing documentation: use a standardized consent checklist (see below).

- Ignoring cultural concerns: ask if any religious or cultural beliefs affect the decision.

Real‑World Example: Removing a Benign Skin Lesion

Emily, a 9‑year‑old, needed a small mole removed before school sports. Her mother signed the consent, but the surgeon also sat with Emily, showed her a picture of the tiny instrument, and let her hold the sterile drape. Emily said she was "okay" after the explanation. The procedure went smoothly, and both mother and child reported feeling respected and informed. Documentation showed the assent question and Emily’s answer, protecting the clinic from any later dispute.

Quick Checklist for Practitioners

- Confirm legal guardian’s identity and authority.

- Use age‑appropriate language and visual aids.

- Explain the procedure, benefits, risks, and alternatives.

- Ask the guardian and child to repeat back key points.

- Document assent status (yes, no, or not applicable).

- Obtain signatures and file the consent form in the EMR.

- Address cultural or religious considerations.

- Provide a contact number for post‑procedure questions.

Comparison: Informed Consent vs. Assent

| Aspect | Informed Consent | Assent |

|---|---|---|

| Legal requirement | Mandatory for all minors (guardian’s signature) | Ethical best practice, not always legally binding |

| Who provides | Legal guardian or court‑appointed custodian | Child, typically age 7 + with appropriate maturity |

| Content focus | Full procedure details, risks, benefits, alternatives | Basic explanation, child’s feelings, willingness |

| Documentation | Signed consent form, EMR entry | Notation of assent/no‑assent in chart |

Frequently Asked Questions

Do I need a signed form if the child agrees?

A signed form from the legal guardian is still required. The child’s verbal agreement (assent) is recorded in the chart but does not replace the formal consent document.

Can a mature minor consent without a parent?

Some states allow mature minors-usually ages 14‑16-to consent to specific procedures if they can demonstrate understanding. Check your state’s statutes and document the competence assessment.

What if the child says “no” but the surgery is urgent?

If the procedure is emergent and delaying it would cause harm, the physician can proceed under the doctrine of implied consent. Still, the guardian must be informed as soon as possible.

How do I handle language barriers during consent?

Use certified medical interpreters, either in‑person or via video. Never rely on family members for translation, as it risks miscommunication.

Is it okay to video‑record the consent conversation?

Recording is permissible only with explicit permission from the guardian (and child, when appropriate) and must comply with HIPAA privacy rules.

Oliver Johnson

October 22, 2025 AT 16:27They sold us a myth, not a process.

Taylor Haven

November 2, 2025 AT 01:27The whole idea of informed consent in pediatric surgery is nothing more than a carefully choreographed performance designed to give the illusion of freedom while the hidden hands of the state pull the strings.

Every paragraph in those glossy checklists is written by bureaucrats who want to create a paper trail that can later be used to blackmail physicians into following a hidden agenda.

They tell us we must obtain a guardian’s signature, but what they forget to mention is that those signatures are later harvested to build databases that track family decisions for future policy manipulation.

The AAP guidelines, lauded as the gold standard, are in fact a joint effort between pediatric societies and pharmaceutical lobbyists keen on expanding their market reach.

When a doctor explains the risks in plain language, they are secretly conditioning the child to accept authority, a subtle form of indoctrination.

The notion of ‘assent’ is a clever euphemism that pretends to respect the child’s autonomy while actually training them to obey without question.

State statutes vary, but they all share the common thread that a parent’s consent can be overridden if the government deems the procedure ‘necessary,’ turning personal choice into a public mandate.

HIPAA is touted as a shield for privacy, yet its clauses are riddled with exemptions that allow health information to be shared with law‑enforcement agencies under the guise of ‘public safety.’

Even the simple act of using a medical interpreter can be a Trojan horse, because interpreters are often vetted by agencies that report back to federal oversight committees.

The checklist that doctors are urged to use is merely a checklist for compliance, not for genuine communication, and it creates a false sense of security.

If a surgeon rushes the conversation, the family may sign without understanding, and the system records that as a successful consent, while the truth is hidden.

The ‘teach‑back’ method sounds innocent, but in practice it becomes a metric for the hospital’s accreditation board, turning empathy into a data point.

Many parents are unaware that by signing, they may be waiving future legal recourse, a fact buried deep in legalese that no one reads.

The whole process is engineered to keep the healthcare industry insulated from accountability, shifting liability onto families who are already vulnerable.

In the end, what we call informed consent is a sophisticated form of social control, packaged in polite language to avoid resistance.

So before you hand over a pen, remember that you might be signing away more than you think, feeding a system that thrives on silent obedience.

Sireesh Kumar

November 12, 2025 AT 11:27Okay, let me break this down for you. The consent checklist isn’t just a piece of paper; it’s a structured way to make sure no detail slips through the cracks, especially when you’re dealing with kids who can’t articulate their fears.

You’ve got to tailor the language to the child’s age – think cartoon drawings for a five‑year‑old and a more detailed explanation for a teenager.

Also, never underestimate the power of the ‘teach‑back’ technique; it’s how you confirm that the guardian actually got it.

And yes, you should always have a certified interpreter on standby if there’s a language barrier – family members aren’t reliable translators.

Bottom line: preparation, clear communication, and documentation are the holy trinity of pediatric consent.

Gary Marks

November 22, 2025 AT 21:27What a circus this consent business has become – a flamboyant display of paperwork that pretends to protect but mostly entertains the bureaucrats.

Doctors are forced to speak in riddles, swapping ‘local anesthesia’ for ‘numbing medicine’ while the parents stare at glossy forms like they’re reading a bedtime story.

The checklist is littered with buzzwords that sound important but do nothing for the trembling kid in the corner.

And let’s not forget the cultural blind spot – you can’t just ignore a family’s religious concerns and hope the procedure goes smoothly.

If a surgeon rushes through the talk, they’re basically committing medical malpractice wrapped in a consent signature.

The whole system rewards speed over empathy, and the hospitals cheer for higher throughput numbers.

Meanwhile, the child’s assent is tossed aside like an unwanted afterthought, a token gesture to appease the ethics board.

Where’s the accountability when a child ends up traumatized because the conversation was a blur?

Bottom line: we need to stop glorifying these sterile checklists and start actually listening.

rose rose

December 3, 2025 AT 07:27Consent forms are just a tool to lock parents into the elite’s agenda.

Emmy Segerqvist

December 13, 2025 AT 17:27Oh my gosh!!! The whole notion of ‘assent’ is a theatrical performance, a grand masquerade!!! Doctors waving their clipboards like scepters, while families sit in the audience, bewildered!!!

Trudy Callahan

December 24, 2025 AT 03:27If we contemplate the essence of consent, we confront the paradox of freedom cloaked in obligation, a dance between authority and autonomy, a veil that both reveals and conceals the truth!!!

Grace Baxter

January 3, 2026 AT 13:27While everyone sings praises of standardized consent, I argue that imposing a uniform script on diverse families is nothing short of cultural imperialism.

The United States prides itself on liberty, yet we hand over that liberty on a clipboard to strangers in white coats.

Every state’s law pretends to protect the child, but underneath lies a federal agenda to homogenize medical practice across the nation.

By demanding the same language for a five‑year‑old in Texas and a teenager in Alaska, we ignore the rich tapestry of regional values.

Moreover, the AAP’s guidelines often masquerade as neutral science while subtly advancing a political agenda that aligns with corporate interests.

The emphasis on ‘assent’ sounds noble, but it is a veiled attempt to co‑opt the child’s voice into the machinery of state control.

Even the HIPAA provisions, touted as guardians of privacy, contain clauses that permit data sharing with federal agencies under vague pretexts.

The reality is that informed consent has become a tool for the central government to monitor and influence family decisions.

If we truly respected freedom, we would hand back the consent form and let families decide without the bureaucratic stranglehold.

In short, the consent checklist is not a safeguard – it’s a soft‑power instrument wielded by the nation’s elite.

Eddie Mark

January 13, 2026 AT 23:27Just watching the consent dance feels like a low‑key jam session where docs try to groove with the kids while staying on beat, no need for extra drama.

Caleb Burbach

January 24, 2026 AT 09:27Let’s turn this process into a win‑win 🌟 – clear, compassionate, and compliant. When physicians use simple language and visual aids, families feel empowered, and the risk of misunderstanding drops dramatically 📉. Accurate documentation then protects both the child and the clinician, creating a trust loop that benefits everyone 😊. Keep the conversation open, keep the checklist handy, and remember that every signed form is a step toward safer care 🚀.