How to Understand Boxed Warning Label Changes Over Time

Jan, 4 2026

Jan, 4 2026

When you pick up a prescription, you might not notice the small, bolded box near the top of the medication guide. But that box - called a boxed warning - could mean the difference between life and death. These aren’t just reminders. They’re the FDA’s strongest safety alerts, reserved for drugs that carry risks of death, hospitalization, or permanent injury. And they don’t stay the same. Over time, these warnings change - sometimes becoming more specific, sometimes removed, sometimes expanded. If you’re a patient, caregiver, or healthcare provider, understanding how and why these changes happen is critical.

What Exactly Is a Boxed Warning?

A boxed warning, also known as a black box warning, is a mandatory label placed at the beginning of a drug’s prescribing information by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). It’s bordered in a thick line - traditionally black, though digital versions may use red or another color - to make it impossible to miss. This isn’t a suggestion. It’s a legal requirement. These warnings appear only when a drug has been linked to serious or life-threatening side effects. That could mean sudden heart failure, severe liver damage, suicidal behavior, or a rare but deadly blood disorder. The FDA doesn’t use them lightly. Between 2001 and 2010, about one-third of all new drugs approved in the U.S. received a boxed warning before they even hit the market. Today, over 32% of all marketed prescription drugs carry at least one.Why Do Boxed Warnings Change?

Boxed warnings aren’t set in stone. They evolve as more real-world data comes in. When a drug is first approved, the FDA relies on clinical trials - often involving a few thousand patients over months or a couple of years. But real life is messier. Millions of people use the drug over decades. Some have other health conditions. Some take other medications. Some are older, younger, or pregnant. That’s when hidden risks show up. For example, the antidepressant warning for children and teens was first added in 2004. It said the drugs might increase suicidal thoughts. By 2006, the FDA updated it to include young adults aged 18 to 24. Why? Because post-marketing data showed the risk wasn’t just in teens - it extended into early adulthood. The warning didn’t just say “risk.” It added: “Monitor patients for clinical worsening, suicidality, and unusual changes in behavior.” That’s precision. That’s what change looks like. Sometimes warnings get removed. Chantix (varenicline), a smoking cessation drug, had a boxed warning for depression and suicidal thoughts from 2009. In 2016, after a massive 8,144-person trial showed no higher risk than placebo, the FDA removed it. That’s rare - but it happens. It means the science caught up with the concern.How to Track Changes Over Time

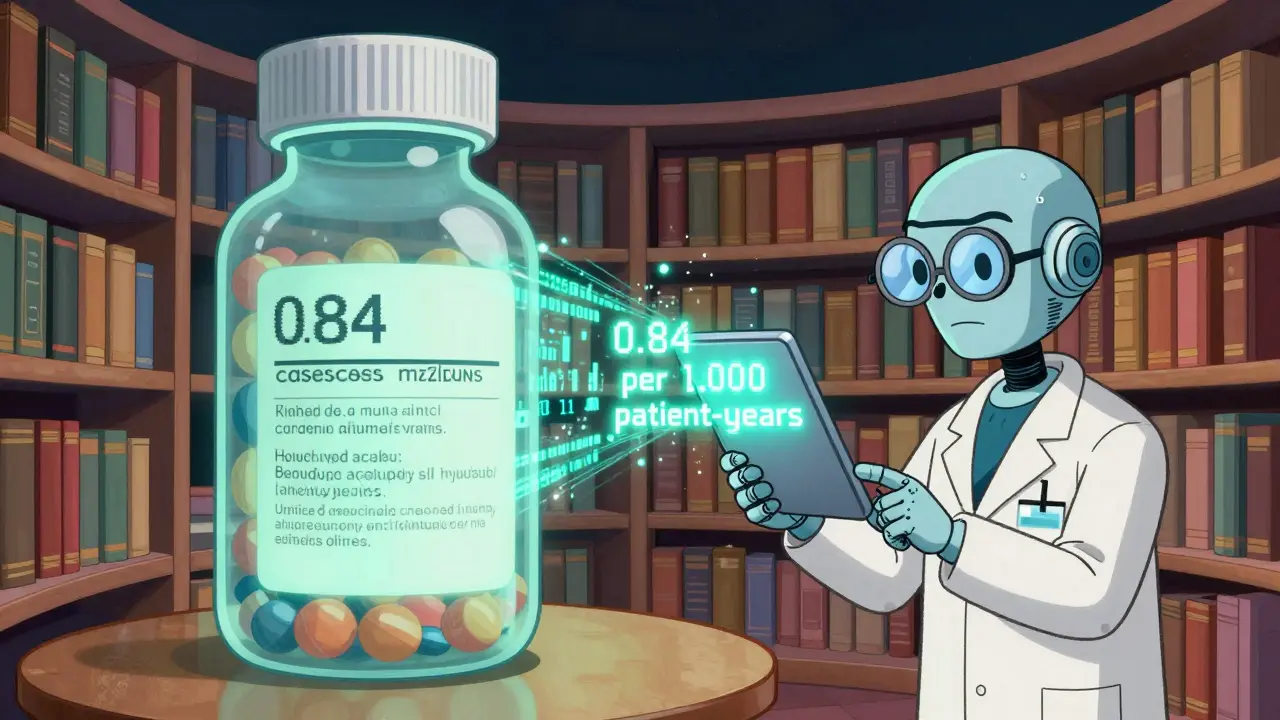

You can’t rely on the label you got in 2020. The FDA updates drug labels continuously. To stay current, you need to know where to look. The Drug Safety-related Labeling Changes (SrLC) database is the official source. It’s free, searchable, and updated every quarter. It includes every change since January 2016 - from minor wording tweaks to full warning overhauls. For example, in April-June 2025, Clozaril’s boxed warning was updated to specify myocarditis risk: “0.84 cases per 1,000 patient-years compared to 0.12 in non-clozapine antipsychotics.” That’s not vague. It’s a number. And it changed the monitoring rules - now cardiac checks are required in the first four weeks. For older changes, use the MedWatch archive. It holds safety updates dating back to the 1990s. And for approval history, Drugs@FDA shows when a drug was approved and what warnings were added at each stage. Pharmacists and clinicians often use the American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy for quarterly summaries. Their April-June 2025 issue listed 17 boxed warning updates across 14 drugs - including new language on neurotoxicity in Unituxin, replacing the older term “neuropathy” to better reflect how the drug damages nerves.

What the Wording Tells You

Don’t just read the warning - decode it. The language has evolved. Early warnings were broad: “May cause liver damage.” Today’s warnings are surgical. Look for:- Specific populations: “In patients over 65,” “in pregnant women,” “in those with kidney disease.”

- Quantified risk: “1 in 1,000,” “0.84 cases per 1,000 patient-years.”

- Actions required: “Mandatory monthly blood tests,” “cardiac monitoring within 4 weeks,” “do not use with other QT-prolonging drugs.”

- Timing: “Risk highest in first 3 months,” “increase after 1 year of use.”

Who’s Affected - And How?

Patients don’t always know about these changes. A 2017 study found only 43.6% of primary care doctors could correctly identify which of their patients’ drugs had a boxed warning. That’s alarming. Family doctors are especially likely to miss them - 76% of them report confusion about when to apply the warning criteria. Specialists, like psychiatrists or oncologists, are better at it, but even they struggle when multiple warnings overlap. On Reddit’s r/Physician thread in March 2024, over 300 doctors shared stories. One said: “I avoid prescribing SSRIs to teens because of the warning - even when they’re severely depressed. I’m scared of the liability.” Another said: “I stopped using Clozaril for years because of the blood monitoring. Then I read the updated warning - the risk is manageable if you follow the schedule.” The flip side? Hospital pharmacists report 89.7% consider boxed warnings essential. For drugs like pimozide (risk of fatal heart rhythm) or clozapine (risk of fatal low white blood cell count), these warnings aren’t just helpful - they’re the only thing preventing deaths.

What’s Changing in the Future

The system is under pressure. More drugs are being approved faster - through programs like Breakthrough Therapy. Between 2012 and 2022, 34.1% of drugs approved under these fast-track programs later got boxed warnings, compared to 22.7% of standard approvals. That means the warnings are catching up to the risks - but often too late. The FDA’s 2025-2027 plan aims to fix that. They’re testing real-time warning updates using electronic health record data. Imagine: a patient develops heart inflammation after starting a new drug. Their EHR flags it. Within weeks, the FDA sees a pattern. Instead of waiting 18 months, the warning updates in real time. Industry analysts predict this will make warnings 60% more specific and 35% shorter. Why? Because right now, too many warnings are too long. Clinicians start ignoring them - a problem called “warning fatigue.” A 2021 study found warnings for rare, catastrophic events (like liver failure) had 78% compliance. Warnings for common, less severe issues (like mild nausea) had only 42% compliance. The goal? Keep the life-saving alerts loud. Quiet down the noise.What You Should Do

If you’re a patient:- Ask your pharmacist: “Does this drug have a boxed warning? Has it changed recently?”

- Don’t assume your old label is still accurate. Check the FDA’s SrLC database if you’re concerned.

- If you’re on a drug with a boxed warning, know the monitoring plan. Blood tests? Heart scans? Frequency? Write it down.

- Bookmark the SrLC database. Check it quarterly.

- Use the Drugs@FDA database to see when your drug’s warning was last updated.

- Don’t rely on memory. Use clinical decision support tools that auto-update with FDA labels.

- Keep a printed copy of the current warning. Don’t trust your memory.

- Track symptoms. If your loved one starts feeling unwell after starting a new drug, check the warning for that exact symptom.

Final Thought

Boxed warnings aren’t meant to scare you off a drug. They’re meant to help you use it safely. The fact that they change means the system is working - science is learning, and safety is improving. But only if you pay attention. The warning on Clozaril didn’t just say “risk of heart inflammation.” It said: “0.84 cases per 1,000 patient-years.” That’s not a guess. That’s data. And it’s why someone’s life might be saved - because a doctor knew to check their heart in week two, not month six. Stay informed. Stay alert. The box changes - so should your understanding.What does a boxed warning mean for my medication?

A boxed warning means the drug has been linked to serious, potentially life-threatening side effects - such as heart failure, liver damage, suicidal behavior, or severe blood disorders. It’s the strongest safety alert the FDA can issue. It doesn’t mean you can’t take the drug, but it does mean you need to understand the risks and follow monitoring steps exactly as directed.

How often do boxed warnings change?

Changes happen regularly - about 25 to 30 new or updated boxed warnings are issued each year. Some updates are minor wording tweaks. Others are major, like adding new risk numbers, expanding the at-risk population, or requiring new tests. The FDA updates its Drug Safety-related Labeling Changes (SrLC) database quarterly, so you can track every change since 2016.

Can a boxed warning be removed?

Yes. If new evidence shows the risk was overestimated or doesn’t exist, the FDA can remove the warning. Chantix (varenicline) had a boxed warning for depression and suicidal thoughts from 2009 until 2016, when a large clinical trial found no increased risk compared to placebo. The warning was removed. This is rare, but it shows the system adapts to real data.

Why do some doctors ignore boxed warnings?

Some doctors experience “warning fatigue” - when too many warnings, especially vague ones, make it hard to focus on the most critical risks. A 2021 study found only 42% of prescribers followed warnings for common side effects, but 78% followed those for rare, deadly ones. Clarity and specificity help. Warnings that say “monitor blood pressure monthly” are easier to follow than “possible adverse effects.”

Where can I find the most current boxed warning for my drug?

The best source is the FDA’s Drug Safety-related Labeling Changes (SrLC) database, updated quarterly and searchable by drug name. You can also check Drugs@FDA for the full prescribing information history. Your pharmacist can also pull up the current label. Never rely on an old printout or a website that isn’t FDA-linked.

Do boxed warnings apply outside the U.S.?

Boxed warnings are a U.S. FDA requirement. Other countries have similar systems - like the UK’s “black triangle” or the EU’s “risk minimization measures” - but the wording, timing, and enforcement differ. A drug with a boxed warning in the U.S. may have a different alert or none at all elsewhere. Always check local regulatory agency guidelines if you’re outside the U.S.

What’s the difference between a boxed warning and a contraindication?

A contraindication means the drug should not be used at all in certain situations - like giving a blood thinner to someone with an active brain bleed. A boxed warning means the drug can be used, but only with extreme caution, monitoring, or restrictions. For example, Clozaril has a boxed warning for low white blood cell count - you can still take it, but you must have monthly blood tests. A contraindication would say “do not use if white blood cell count is below X.”

Beth Templeton

January 6, 2026 AT 10:39Ryan Barr

January 7, 2026 AT 23:55Matt Beck

January 8, 2026 AT 20:36Tiffany Adjei - Opong

January 10, 2026 AT 00:32Cam Jane

January 11, 2026 AT 20:55Amy Le

January 12, 2026 AT 20:52Stuart Shield

January 14, 2026 AT 12:55Jeane Hendrix

January 15, 2026 AT 17:32Katelyn Slack

January 16, 2026 AT 05:13Melanie Clark

January 17, 2026 AT 15:38Lily Lilyy

January 18, 2026 AT 17:54Dana Termini

January 20, 2026 AT 09:56