How Medications Enter Breast Milk and What It Means for Your Baby

Feb, 19 2026

Feb, 19 2026

When a nursing mother takes a medication, it doesn’t just stay in her body. Some of it ends up in her breast milk-and that’s something many new parents worry about. But here’s the truth: most medications are safe to take while breastfeeding. The real question isn’t whether drugs get into milk-it’s how much, how fast, and what it means for your baby.

How Medications Get Into Breast Milk

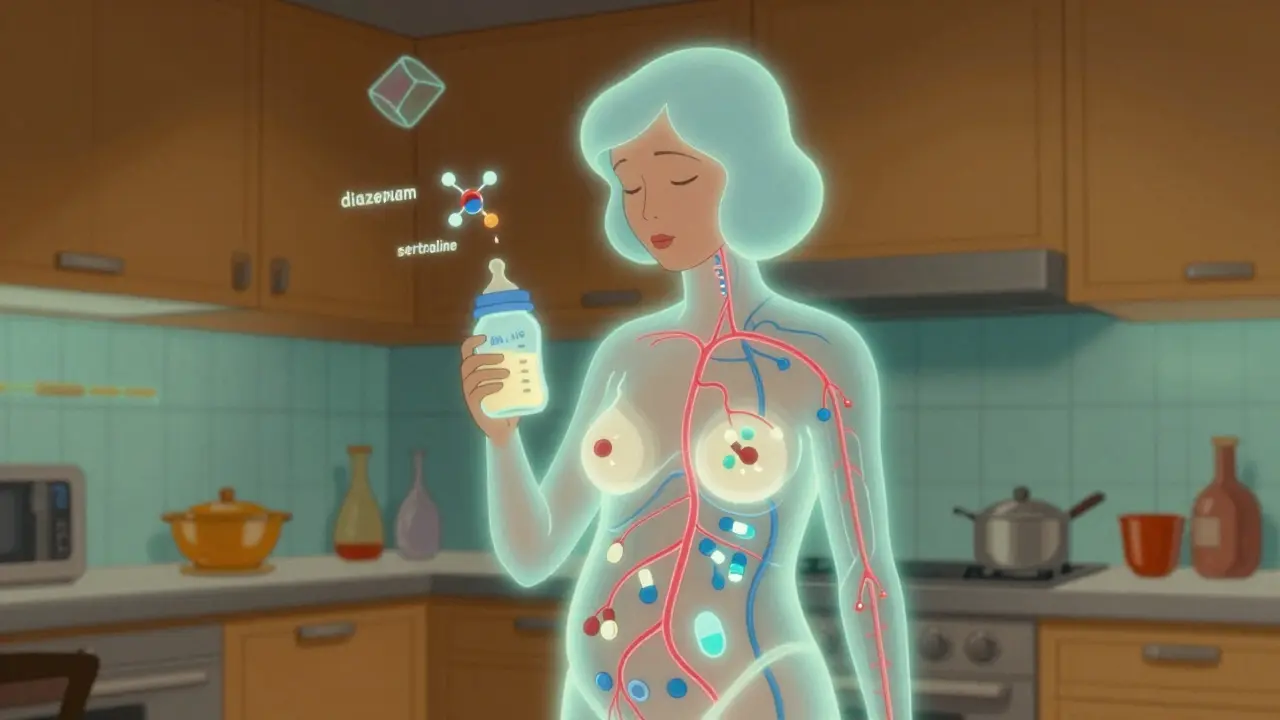

Medications don’t magically appear in breast milk. They move there through natural processes in the mother’s body. About 75% of the time, this happens through passive diffusion. Think of it like a sponge soaking up water. When a drug circulates in the mother’s bloodstream, it slowly moves from areas of higher concentration (her blood) to lower concentration (her milk), crossing the membranes between blood vessels and milk-producing cells in the breast. The rest of the transfer-about 25%-comes from two other ways: carrier-mediated transport and active secretion. Some drugs, like cimetidine or ranitidine, hitch a ride on special protein shuttles in the breast tissue. Others are actively pumped into milk by the body’s own transport systems. This is why not all drugs behave the same way. Two key factors control how much ends up in milk: size and solubility. Drugs under 300 daltons (a unit of molecular weight) slip through easily. Lithium, at just 74 daltons, moves freely. But big molecules like heparin (15,000 daltons) barely get in-less than 0.1% of the dose makes it into milk. Lipid-soluble drugs, like diazepam, also cross more readily because breast milk is fatty. That’s why diazepam can reach milk concentrations 1.5 to 2 times higher than in the mother’s blood. Water-soluble drugs, like gentamicin, barely make a dent-less than 0.1% of the dose shows up in milk.Protein Binding and pH: The Hidden Players

You might think if a drug is in the blood, it’s automatically in the milk. But that’s not true. The more a drug sticks to proteins in the mother’s blood, the less is free to enter milk. Warfarin, for example, is 99% bound to proteins. That means less than 0.1% gets into milk. Sertraline, though also highly bound, still transfers enough to be measurable because it’s not quite as tightly held. Then there’s pH. Breast milk is slightly more acidic than blood (pH 7.0-7.4 vs. 7.4). This creates a phenomenon called ion trapping. Weak bases-drugs with a high pKa like amitriptyline (pKa 9.4)-get pulled into milk and get stuck there. The result? Milk levels can be 2 to 5 times higher than in the mother’s blood. That’s why some antidepressants and antihistamines show up more prominently in milk than others.Timing Matters: The First Days Are Different

Right after birth, your body is still adjusting. During the first 4 to 10 days, the tight junctions between milk-producing cells are still loose. Think of them like gaps in a fence. That lets in not just antibodies but also larger molecules-including some medications-that wouldn’t normally pass later. After day 10, those junctions seal shut. Milk becomes a more selective filter. That’s why some drugs given right after delivery (like antibiotics or pain relievers) might show up more in early milk than they would weeks later.

How Much Does the Baby Actually Get?

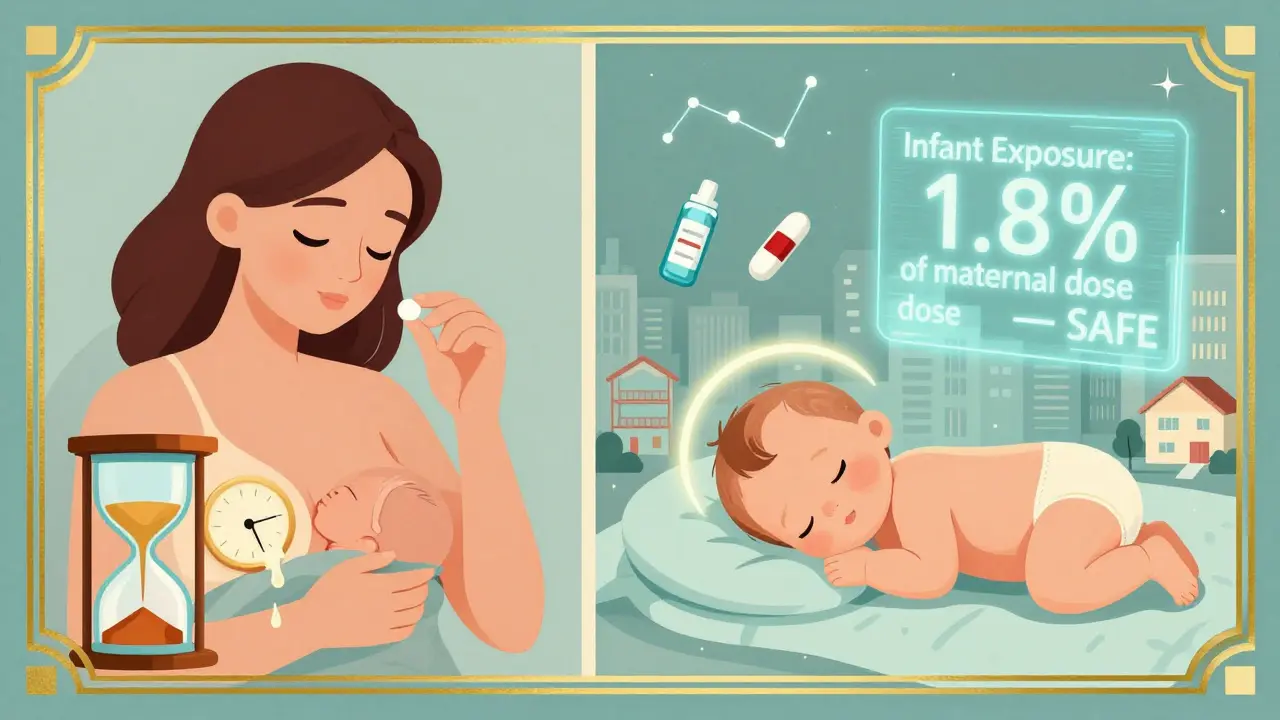

It’s not about how much is in the milk-it’s about how much the baby absorbs and how their body handles it. Most drugs in milk are present in tiny amounts: usually 0.5% to 3% of the mother’s weight-adjusted dose. For antibiotics like amoxicillin or gentamicin, that’s barely noticeable. Even for antidepressants like sertraline, infant exposure is typically 1-2% of the mother’s dose. But some drugs are different. Benzodiazepines like diazepam can reach 5-10% of the maternal dose. And because diazepam has a long half-life in newborns (up to 100 hours), it can build up over time. That’s why doctors monitor infants on high-dose maternal regimens-especially if mom is taking more than 10 mg per day. The CDC and the InfantRisk Center say: if the infant receives less than 10% of the mother’s dose (adjusted for weight), the risk is generally low. For antibiotics, the goal is undetectable levels in the baby’s blood. For antidepressants, levels below 10% of the therapeutic adult dose are considered safe.Drugs That Are Risky-and Why

Not all drugs are created equal. Some have clear red flags:- Radioactive iodine-131 (used in thyroid scans or treatment): This one is a hard no. It concentrates in the baby’s thyroid and can damage it. Breastfeeding must stop for weeks.

- High-dose estrogen contraceptives (over 50 mcg ethinyl estradiol): These can cut milk supply by 40-60% within 72 hours. Progestin-only pills are safer.

- Bromocriptine: This drug shuts down milk production. It’s used intentionally to stop lactation-not for treating other conditions while breastfeeding.

- Chronic high-dose lithium: Can cause toxicity in infants, including lethargy and poor feeding. Requires careful monitoring.

When to Time Your Dose

Timing your medication can make a big difference. If you take a pill right after breastfeeding, you give your body time to clear most of it before the next feeding. For drugs with short half-lives (like ibuprofen or amoxicillin), waiting 3-4 hours reduces infant exposure by 30-50%. That’s not a trick-it’s science. For long-acting drugs, like diazepam or phenobarbital, the timing helps less. In those cases, monitoring the baby’s behavior becomes more important than timing. Look for signs: excessive sleepiness, poor feeding, fussiness. If you notice these, talk to your provider. A simple blood test for the infant’s drug level can give clarity.

What the Data Shows

About 56% of breastfeeding mothers take at least one medication. The most common? Antibiotics (28.5%), pain relievers (22.1%), and antidepressants (18.3%). Sertraline is the #1 prescribed antidepressant during breastfeeding-used in over 3 out of every 100 breastfeeding women each month. Yet, medication concerns are the third most common reason mothers stop breastfeeding early-after perceived low milk supply and nipple pain. A 2022 study found that 15-30% of women quit breastfeeding unnecessarily because they were told to stop a medication that was actually safe. The good news? Only 1-2% of medications are truly contraindicated. The rest can be used safely with smart timing, monitoring, or dose adjustments.Tools That Help

The InfantRisk Center, founded by Dr. Thomas Hale, has built the most trusted database on medication use during lactation. Their LactMed app (version 3.2, updated January 2023) uses 12 pharmacokinetic factors to give real-time risk scores. It’s now used by OBs, pediatricians, and pharmacists across the U.S. The FDA also changed its rules in 2023: all new drugs must now include lactation exposure data in their labeling. This means better, clearer guidance for prescribers and moms alike.What You Should Do

If you’re breastfeeding and need medication:- Don’t stop breastfeeding without checking with your provider.

- Tell your doctor you’re breastfeeding-don’t assume they know.

- Ask: “Is this drug safe in breast milk?” and “What’s the infant exposure level?”

- Take meds right after a feeding, not before.

- Watch your baby for changes in sleep, feeding, or mood.

- Use trusted resources like the InfantRisk Center or LactMed app-avoid random internet advice.

Arshdeep Singh

February 21, 2026 AT 05:23Danielle Gerrish

February 22, 2026 AT 11:41Maddi Barnes

February 22, 2026 AT 16:08Jonathan Rutter

February 24, 2026 AT 04:15Jana Eiffel

February 24, 2026 AT 13:33Tommy Chapman

February 26, 2026 AT 07:27Laura B

February 28, 2026 AT 01:33Hariom Sharma

March 1, 2026 AT 13:19Nina Catherine

March 1, 2026 AT 22:17Courtney Hain

March 3, 2026 AT 04:10Robert Shiu

March 4, 2026 AT 23:10Jeremy Williams

March 5, 2026 AT 11:31Chris Beeley

March 5, 2026 AT 21:48