Erosive Esophagitis Complications: Risks, Symptoms, and Management

Sep, 24 2025

Sep, 24 2025

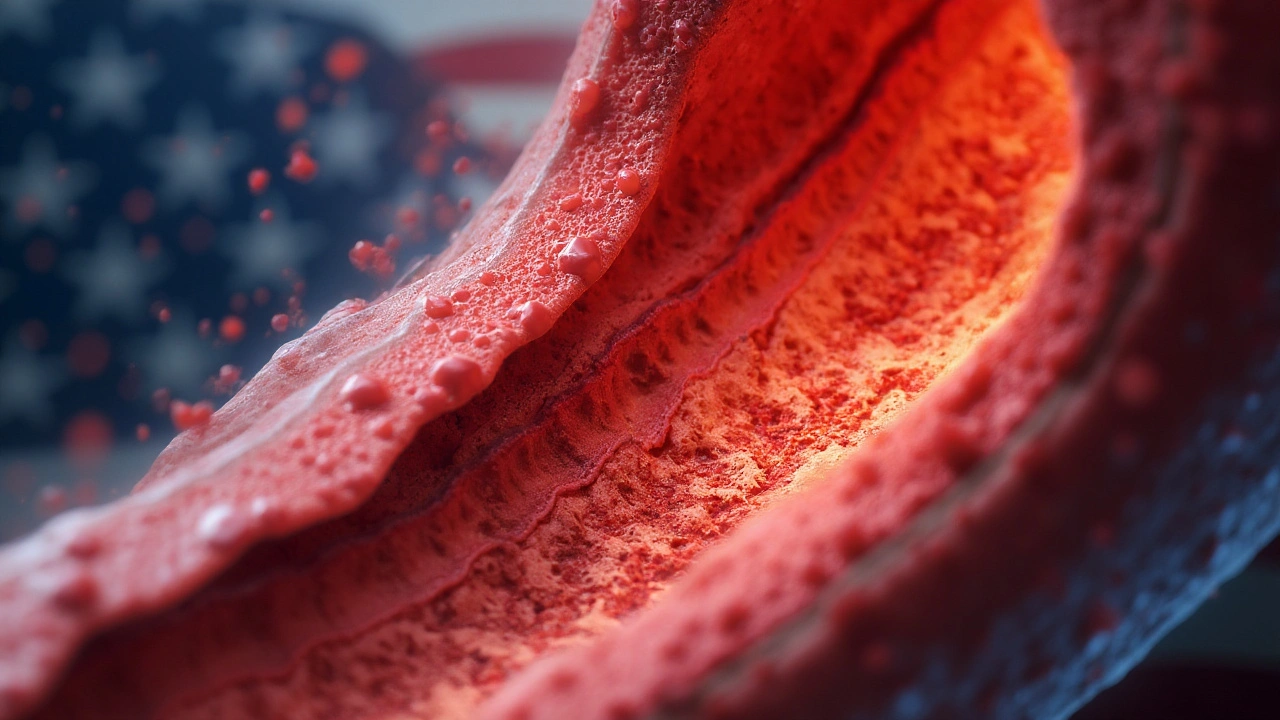

Erosive Esophagitis is a type of inflammation where stomach acid repeatedly damages the lining of the esophagus, leading to erosions and ulcerations. This condition often stems from chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and can set the stage for several serious complications.

Quick Take

- Persistent acid exposure can lead to Barrett's esophagus, strictures, ulcers, and even cancer.

- Symptoms such as difficulty swallowing, chest pain, or unexplained weight loss signal complications.

- Early detection through endoscopy and targeted therapy (e.g., PPIs) dramatically lowers risk.

- Lifestyle changes-weight control, diet, and head‑of‑bed elevation-support medical treatment.

- Regular monitoring is essential; many complications are silent until advanced.

Why Complications Occur

The esophagus lacks the protective mucus layer found in the stomach. When acid reflux is frequent, the squamous epithelium can become damaged, triggering a cascade of cellular changes. Inflammatory mediators like prostaglandins and cytokines promote tissue remodeling, which may evolve into metaplasia (Barrett's), fibrosis (stricture), or ulceration. If DNA damage accumulates, dysplasia and ultimately cancer can arise.

Common Complications Explained

Below are the most frequently encountered outcomes of untreated or poorly managed erosive esophagitis.

Barrett's Esophagus is a precancerous condition where the normal squamous cells are replaced by columnar cells that resemble those in the intestine. It occurs in roughly 10‑15% of chronic GERD patients and increases the lifetime risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma by 30‑125 times.

Patients often report persistent heartburn despite medication, occasional sour taste, or subtle dysphagia. Surveillance endoscopy every 3‑5 years is the standard to catch dysplasia early.

Esophageal Stricture is a narrowing of the esophageal lumen caused by scar tissue contraction after repeated inflammation. The prevalence in severe erosive disease ranges from 5‑10%.

Typical signs include progressive difficulty swallowing solid foods, a sensation of food getting stuck, and occasional chest discomfort. Endoscopic dilation is the first‑line therapy, often combined with high‑dose proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) to prevent re‑scarring.

Esophageal Ulcer is a deep break in the mucosal surface that can bleed or perforate if left untreated. Ulcers appear in up to 8% of patients with severe erosive esophagitis.

Sharp retrosternal pain that worsens after meals and occasional vomiting of blood (hematemesis) are red flags. High‑dose PPIs and mucosal protective agents (e.g., sucralfate) promote healing, while endoscopic evaluation confirms size and rules out malignancy.

Esophageal Cancer is a malignant tumor arising from the esophageal lining, most often adenocarcinoma linked to Barrett's. Although overall incidence is low (≈5 per 100,000), it carries a 5‑year survival below 20% when diagnosed late.

Warning signs include progressive dysphagia to liquids, unexplained weight loss, chronic cough, and hoarseness. Early detection hinges on regular surveillance of Barrett's and prompt investigation of new symptoms.

How to Diagnose Complications

Accurate diagnosis relies on a combination of symptom assessment, imaging, and direct visualization.

- Upper Endoscopy (EGD): The gold standard for visualizing erosions, ulcers, strictures, and Barrett's. Biopsies are taken to assess dysplasia.

- Barium Swallow: Useful for detecting strictures or motility disorders when endoscopy is not immediately available.

- pH Monitoring: Quantifies acid exposure; a pH < 4 for >6% of a 24‑hour period confirms pathological reflux.

- Manometry: Evaluates esophageal motility, especially if dysphagia persists after dilation.

Treatment Strategies for Each Complication

Management is a blend of medication, procedural intervention, and lifestyle modification.

Barrett's Esophagus

- High‑dose Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) therapy to suppress acid.

- Endoscopic eradication (radiofrequency ablation or endoscopic mucosal resection) for dysplastic segments.

- Surveillance endoscopy every 3-5 years for non‑dysplastic Barrett's; more frequent if dysplasia is present.

Esophageal Stricture

- Endoscopic dilation using bougies or balloons; repeat sessions may be needed.

- Adjunctive PPI therapy to reduce recurrence.

- Surgical resection (esophagectomy) is reserved for refractory cases.

Esophageal Ulcer

- High‑dose PPIs (e.g., omeprazole 40mg BID) for 8‑12 weeks.

- Sucralfate or alginate suspensions for mucosal coating.

- Endoscopic hemostasis if active bleeding is observed.

Esophageal Cancer

- Multidisciplinary approach: surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy.

- Neoadjuvant chemoradiation improves resectability.

- Targeted therapies (e.g., HER2 inhibitors) for selected adenocarcinomas.

Prevention: Lifestyle & Long‑Term Care

Even if you’re on medication, habits play a huge role.

- Maintain a healthy weight; excess abdominal pressure worsens reflux.

- Eat smaller, non‑spicy meals; avoid citrus, chocolate, caffeine, and alcohol near bedtime.

- Elevate the head of the bed 6‑8 inches; gravity reduces nocturnal reflux.

- Quit smoking; nicotine relaxes the lower esophageal sphincter.

- Regular follow‑up with your gastroenterologist; early detection saves lives.

Related Concepts and Next Steps

Understanding erosive esophagitis opens doors to broader topics such as:

- Hiatal Hernia - a structural defect that predisposes to reflux and thus to erosive disease.

- Acid Reflux Pathophysiology - the physiological mechanisms behind lower esophageal sphincter failure.

- Esophageal Motility Disorders - conditions like achalasia that can coexist with reflux and affect symptom presentation.

- Dietary Management for GERD - evidence‑based food choices that reduce acid exposure.

After mastering the complications, you might explore "Advanced Endoscopic Therapies for Barrett's" or "Surgical Options for Refractory GERD" as logical next reads.

Comparison of Major Complications

| Complication | Prevalence in Severe Erosive Disease | Risk of Cancer | Typical First‑Line Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barrett's Esophagus | 10‑15% | 30‑125× increased adenocarcinoma risk | High‑dose PPI + endoscopic surveillance |

| Esophageal Stricture | 5‑10% | Low direct cancer risk; may mask dysplasia | Endoscopic dilation + PPI |

| Esophageal Ulcer | ≈8% | Rare progression to cancer | High‑dose PPI ± sucralfate |

| Esophageal Cancer | ≤0.5% (overall), higher with Barrett's | - | Multimodal therapy (surgery, chemo, radiation) |

Key Takeaway

If you’ve been diagnosed with erosive esophagitis complications, proactive monitoring, aggressive acid suppression, and lifestyle tweaks can keep you from sliding into more serious territory. Early endoscopic assessment isn’t just a formality-it’s a lifeline.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can erosive esophagitis cause cancer without developing Barrett’s?

Yes, though rare. Persistent ulceration and chronic inflammation can lead to dysplasia independently, but the majority of esophageal adenocarcinomas arise from Barrett's metaplasia.

How often should I get an endoscopy if I have Barrett’s?

Guidelines recommend surveillance every 3‑5 years for non‑dysplastic Barrett’s. If low‑grade dysplasia is found, repeat every 6‑12 months, and high‑grade dysplasia warrants immediate therapeutic intervention.

Are over‑the‑counter antacids enough to prevent strictures?

OTC antacids provide short‑term relief but don’t keep acid levels low enough to halt scar formation. Prescription PPIs are needed to reduce the risk of stricture development.

What lifestyle changes have the biggest impact on reflux?

Losing excess weight, elevating the head of the bed, and avoiding trigger foods (caffeine, chocolate, citrus, spicy meals) are the most effective. Quitting smoking and limiting alcohol further reduce acid episodes.

When should I call my doctor urgently?

Seek immediate care if you experience vomiting blood, black tarry stools, sudden inability to swallow liquids, or severe chest pain that doesn’t improve with antacids. These may signal bleeding, perforation, or advanced cancer.

Ronald Thibodeau

September 25, 2025 AT 06:37Wow, another ‘just take a PPI and call it a day’ article. Real helpful. Ever heard of people who can’t afford $500/month for brand-name PPIs? Or those who get rebound acid from stopping them? You talk about ‘aggressive acid suppression’ like it’s magic. Meanwhile, my cousin’s esophagus is still shredded because his insurance denied the endoscopy for ‘non-urgent’ symptoms. This isn’t a textbook-it’s a survival guide for people who can’t afford to be sick.

Shawn Jason

September 25, 2025 AT 19:29It’s fascinating how the body tries to protect itself-even by turning squamous cells into intestinal ones. Barrett’s isn’t just a ‘precancerous condition,’ it’s an adaptation. The esophagus is saying, ‘I can’t handle acid, so I’ll become something that can.’ We treat it like a failure, but maybe it’s just biology doing its best with bad options. What if we stopped seeing these changes as ‘mistakes’ and started seeing them as signals? The real tragedy isn’t the metaplasia-it’s that we wait until the body screams before we listen.

Monika Wasylewska

September 27, 2025 AT 00:14My mom had strictures after 10 years of GERD. She didn’t realize it was getting worse until she couldn’t eat rice. PPIs helped, but the real game-changer? Sleeping on a wedge. No joke. And cutting out chocolate. Who knew?

Jackie Burton

September 28, 2025 AT 23:31Let’s be real-this whole ‘Barrett’s surveillance’ thing is a Big Pharma money loop. Endoscopies cost $3k, PPIs are $100/month, and they’ll keep you on them forever. Meanwhile, the FDA knows PPIs increase risk of C. diff, kidney disease, and bone fractures. But hey, let’s just keep scanning and dosing while the GI industry rakes in billions. And don’t get me started on ‘endoscopic ablation’-that’s just expensive laser tag with your esophagus. Wake up. This isn’t medicine. It’s a subscription model.

Philip Crider

September 29, 2025 AT 02:53Yo, this post is 🔥 but I gotta say-why isn’t anyone talking about the gut-brain axis here? 🤯 Like, stress literally makes your LES relax harder. I had erosive esophagitis after my divorce. PPIs? Barely helped. Therapy? Changed everything. Also, I typo’d ‘PPIs’ as ‘PPIs’ like 3 times but you get it 😅. Bottom line: your esophagus isn’t just a pipe-it’s a mirror. Fix your life, not just your acid. And yes, I still eat spicy food. No regrets. 🌶️❤️